Thursday, December 15, 2011

Prospect v. Meadows: Gambit Play

On 3rd Board, Rolling Meadows Jonathan Phillips played the Evans Gambit (1.e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3.Bc4 Bc5 4.b4!? against Caleb Royse. This is a dangerous opening where White sacrifices a pawn for rapid development. I know that it's dangerous because I lost against it last weekend. However, White got in trouble when he moved a piece twice with 9.Ng5? before he had moved them all once.

It is always fun to attack something that seems to be under-defended, however, you should always assume that your opponent is going to see the threat and respond to it. If your opponent is forced to put his pieces on awkward squares where they inhibit his development, that may be good reason to violate the general opening principle of "move every piece once before you move any piece twice." In fact, White frequently has the opportunity to make those kind of moves in the Evans Gambit. In this case however, Black meets the threat with a move that he was eager to make anyway, 9...0-0. White would have been better completing his mobilization with 9.d4.

Just a Pawn

One of the things that makes chess so frustrating is how a minor oversight can have such dire consequences. On 3rd Board, Meadows' Ben Kusnierz had played very solidly against Echo Genc for twenty-three moves before he missed a knight fork that netted Echo a pawn. Unfortunately for Ben, the loss of that one pawn left him with two isolated pawns which soon became targets.

It is always fun to attack something that seems to be under-defended, however, you should always assume that your opponent is going to see the threat and respond to it. If your opponent is forced to put his pieces on awkward squares where they inhibit his development, that may be good reason to violate the general opening principle of "move every piece once before you move any piece twice." In fact, White frequently has the opportunity to make those kind of moves in the Evans Gambit. In this case however, Black meets the threat with a move that he was eager to make anyway, 9...0-0. White would have been better completing his mobilization with 9.d4.

Just a Pawn

One of the things that makes chess so frustrating is how a minor oversight can have such dire consequences. On 3rd Board, Meadows' Ben Kusnierz had played very solidly against Echo Genc for twenty-three moves before he missed a knight fork that netted Echo a pawn. Unfortunately for Ben, the loss of that one pawn left him with two isolated pawns which soon became targets.

Prospect v. Meadows: Imbalances

Prospect finished its season with a 46-22 victory over Rolling Meadows that featured a very interesting material imbalance on 1st Board, where Prospect's Robert Moskwa reached an ending with two knights and six pawns against Anthony Leone's rook, bishop and three pawns. There is nothing strange about unusual imbalances in high school chess, but they are usually accidental rather than intentional. Unfortunately, the short time controls can make it very difficult to find the right path in unfamiliar waters.

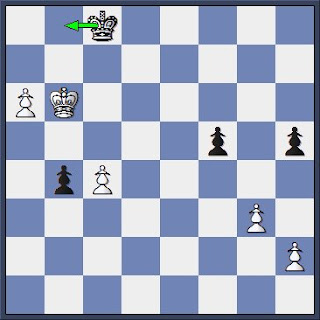

What should White do here?

Hint: As I often say, a basic principle of the endgame is "Pieces before Pawns." I.e., pawns that are pushed before the pieces are in position to support them often become weak. Therefore, unless you are in a pure pawn race, it is usually better to improve the position of your pieces before you try to advance your pawns. The converse of that principle is that your opponent's pawns may become weak if you can get him to advance them before his pieces are ready to support them.

I will post the analysis later.

Hint: As I often say, a basic principle of the endgame is "Pieces before Pawns." I.e., pawns that are pushed before the pieces are in position to support them often become weak. Therefore, unless you are in a pure pawn race, it is usually better to improve the position of your pieces before you try to advance your pawns. The converse of that principle is that your opponent's pawns may become weak if you can get him to advance them before his pieces are ready to support them.

I will post the analysis later.

Wednesday, December 14, 2011

King, Rook and Rook's Pawn vs. King and Rook

Consider the following two positions which were inspired by Robert Moskwa's recent game with the World Under 8 Champion, Awonder Liang. White has just checked the Black king with his rook and Black has the choice of moving away from the White king and pawn with 1...Kd7 or towards them with 1...Kb6. The only difference is that the White rook is on c4 in the first and c3 in the second. Both positions are theoretical draws if Black makes the correct choice. See if you can figure what the right move is in each case before you look at the analysis in the next post.

Battle of the Titans

Coach Neil Mott of Rolling Meadows reminded me that I have been somewhat remiss in updating my blog and he particularly expressed an interest in seeing the showdown between the two top players in the conference, Buffalo Grove's Matt Wilber and Prospect's Robert Moskwa. I wish it were a more exciting game than it was. Robert achieved a solid position with the Black pieces out of the opening but over optimistically snatched what only looked like a free pawn on his 17th move. He quickly found himself down a pawn in a cramped position which is the last thing you want against a player of Matt's abilities. Matt kept tight control of the position and ground out the win.

Wednesday, December 7, 2011

Why Chess Drives You Nuts

This is the position after Echo Genc's 17.exf7+ against Schaumburg's Charles Jaris. Jaris played 17...Rxf7, which is objectively the best move. However, if Black had played the weaker 17...Kh8, what would have been White's winning move?

Thursday, November 17, 2011

Sometimes a Pawn Gets in the Way

It's Black's move. Which position does he prefer?

Interestingly, Black is much better off with one less pawn. In the first position, he simply plays 1.Kc4 and 2.Kb5 which forces the knight to give up its protection of the White pawn. Once White's pawn is gone, the position is drawn.

In the second position, Black is dead lost because his pawn prevents his King from reaching a square from which it can attack both the knight and the pawn. After 1...Kc6 2.Kh4 Kb6, the White knight moves to safety with 3.Nc5. Now it will take three moves for the Black king to attack the White pawn, 3...Kc6, 4...Kd5, and 5...Kc4, whereupon the White knight protects the pawn with Na6, when it will take the Black king another three moves to get back to b6. White can use this time to pick off the Black h-pawn after which it comes over to gang up on the Black b-pawn.

Interestingly, Black is much better off with one less pawn. In the first position, he simply plays 1.Kc4 and 2.Kb5 which forces the knight to give up its protection of the White pawn. Once White's pawn is gone, the position is drawn.

In the second position, Black is dead lost because his pawn prevents his King from reaching a square from which it can attack both the knight and the pawn. After 1...Kc6 2.Kh4 Kb6, the White knight moves to safety with 3.Nc5. Now it will take three moves for the Black king to attack the White pawn, 3...Kc6, 4...Kd5, and 5...Kc4, whereupon the White knight protects the pawn with Na6, when it will take the Black king another three moves to get back to b6. White can use this time to pick off the Black h-pawn after which it comes over to gang up on the Black b-pawn.

Saturday, October 29, 2011

Rules FAQ: Offering and Accepting Draws

What is The Proper Way to Offer a Draw?

Make your move on the board. Say, "I offer a draw." Press your clock. (Rule 12-2-1)

What Happens if the Proper Procedure Is Not Followed?

Two minutes can be added to the opponent of the player making the improper offer and the offer can still be accepted. (Rule 12-3-4) (I personally believe that this is excessive since the recipient of the improper offer suffers no harm. It is unlikely that this penalty would be imposed in an MSL match. Nonetheless, that's the IHSA rule and you should expect the penalty to be enforced at state and other tournaments. To the best of my recollection, USCF rules do not penalize improper draw offers.)

What if Your Opponent Offers a Draw Before He Moves?

You are entitled to see your opponent's move before making your decisions on whether to accept. If you wish to be polite, you can say "Play your move first." If you don't wish to be helpful, you can simply remain silent until your opponent makes his move. (Rule 12-3-3)

Can Your Opponent Withdraw His Offer?

No. Once the offer is made it cannot be withdrawn. If your opponent offers a draw before making his move and then finds a move that absolutely crushes you, he cannot withdraw the offer. Once he makes the crushing move on the board, you can say "I accept." (Rule 12-2-3)

How Do You Decline a Draw Offer?

There are two ways to decline a draw offer. (1) Make a move. (2) Say "I decline." (Rule 12-2-2)

Should You Ever Decline a Draw Without Making a Move?

NO! If you say "I decline" before you have chosen a move, there is always a chance that you will find upon further reflection that your position is worse than you thought. However, once you have declined the offer you are out of luck. If you are practically certain that you are going to decline the offer, you might wish to say something like "Let me look at it." When, you are ready to make your move, you can also say "I decline" if you wish. There is no reason to orally decline the draw offer before you are ready to make your move on the board.

What Constitutes a Draw Offer?

In addition to "I offer a draw" or "Draw?", any attempt to determine whether an opponent might be interested in agreeing to a draw may be treated as a draw offer. For example, if your opponent says, "Do you think I can win this?" you may respond "I accept a draw." (Rule 12-4)

Can You Offer a Draw After an Offer Has Been Declined?

Making repeated draw offers may be penalized as a attempt to distract your opponent. If a draw offer has been declined, another offer should not be made unless the position has changed substantially or a player has some other reason to think that his opponent might respond differently. (Rule-17-8-1)

Prospect Falls to Fremd (2): Knowing the Score

The result against Fremd could very easily have gone the other way if the players on 4th Board not agreed to a draw. At the time, Prospect's Ekrem Genc had good winning chances against Fremd's Chang. Unfortunately, he was running low on time and he lacked confidence in his ability to play the endgame correctly.

This position is winning for White, but it is going to take some work. After something like 48.b4 Bd2 49.a6, Black can give up his bishop for the a-pawn and b-pawn with 49...Bxb3 50.Rxb3 Rxa6. White's two extra pawns on the other side of the board should be enough to win, but it's going to take a while. With his king in front of the pawns and his rook checking from the side and from behind, Black could have held out for awhile. Nonetheless, given that Prospect needed a win to win the match, Ekrem should have kept playing. On the other hand, the fault does not lie entirely with the player.

A Coaching Failure.

When a match is down to one or two games, IHSA rules allow the coach to give a Communication Card to a tournament steward to give to a player telling him what the score of the match is and the effect that his result will have on determining the outcome of the match. Unfortunately, this did not occur to me until Ekrem was low on time and I did not know what the correct procedure was for going about it. As a result, I had to talk to Mr. Barrett about it and before we could get it figured out, the players had agreed to the draw.

Ideally, a player should always try to apprise himself of how the match stands before he agrees to a draw. IHSA rules also permit a player to have the steward pass a Communication Card to a coach in order to find out how the match stands. Moreover, a player can initiate a communication regardless of how many games are still being played in the match. A player can also get up and look at the match score sheet. However, a player with less than four minutes on his clock cannot reasonably be criticized if he decides that trying to figure out how the match stands is not a wise use of his remaining time.

Mr Barrett and I should have been prepared to communicate the score if the need arose.

Why Game 60 Sucks

Game 60 is a convenient time control if you want to hold a match after the school day ends without getting the players home so late that they can't have dinner and do their homework. G60 is also handy if you want to complete a seven round tournament for the state championship in two days. However, when it comes to developing endgame technique, G60 sucks. On those rare occasions where both sides play well enough to reach an endgame where the result is in doubt, it is even rarer for either player to have enough time remaining to do the position justice. On top of that, players are often so low on time that they quit keeping score in the ending making it very difficult to go over the game and learn from mistakes.

One of the best reasons for joining the United States Chess Federation is to get the opportunity to play in some longer time controls. The Continental Chess Association runs three area events each year, the Chicago Open, the Chicago Class, and the Midwest Class, that use a time control of forty moves in two hours filed by one hour sudden death (40/2, SD/1). That means that each side has up to three hours to complete the game which usually leaves enough time to devote some thought to the ending. The Illinois Open, the Illinois Class, and Tim Just's Winter Open use game in ninety minutes with a thirty second increment (G90 inc 30) which means that thirty seconds get added to each players clock on each move. In a game that goes sixty moves, each side will have two hours. This doesn't always leave time for deep thought in the ending but at least the thirty seconds per move allows the player to keep score for later review. Up in Madison at the University of Wisconsin Chess Club, they occasionally run events with a generous 45/2, 25/1, SD/1.

The downside to the USCF events is that the longer time controls tend to be bigger events with larger entry events. Nevertheless, the key to improvement in all phases of the game is to play slower games.

The Zwischenzug

Despite Ekrem's professed lack of confidence in his endgame skills, he actually found a couple of moves that demonstrate excellent chess thinking. "Zwischenzug" is a German word meaning "in between move." It refers to a quiet move that is played in an otherwise forcing sequence. They are very easy to overlook when calculating variations. Ekrem found a very nice one on his 36th move.

The most obvious move here is 36.Rxb5 when Black will find it very difficult to promote his remaing h-pawn. Running low on time, no one could blame White for playing this move immediately. However, Ekrem saw that 36...Rxc2 threatened both White's a-pawn and f-pawn. He also saw that the Black b-pawn wasn't going anywhere so he played the zwischenzug 36.Re5! driving the bishop away from e1. After 36...Bd2 37.Rxb5 Rxc2, White could play 38.a4 without worrying about his f-pawn. This is the kind of thinking that produces good endgame play.

Basic Endgame Positions

In order to succeed in endings at short time controls, it is necessary to have some of the basic positions down pat such as The Wrong Colored Bishop and Rook Pawn. A lone king can draw against a king, bishop and a-pawn or king, bishop, and h-pawn if the bishop does not control the queening square.

This is the position that White would have had with both rooks and all his pawns gone. It is a draw because there is no way that Black will ever be able to evict the White king from h1. The quick reason that Ekrem should have kept playing is that even if he managed to lose all five of his pawns, all White needed to do was trade rooks in order to reach a dead drawn position.

This position is winning for White, but it is going to take some work. After something like 48.b4 Bd2 49.a6, Black can give up his bishop for the a-pawn and b-pawn with 49...Bxb3 50.Rxb3 Rxa6. White's two extra pawns on the other side of the board should be enough to win, but it's going to take a while. With his king in front of the pawns and his rook checking from the side and from behind, Black could have held out for awhile. Nonetheless, given that Prospect needed a win to win the match, Ekrem should have kept playing. On the other hand, the fault does not lie entirely with the player.

A Coaching Failure.

When a match is down to one or two games, IHSA rules allow the coach to give a Communication Card to a tournament steward to give to a player telling him what the score of the match is and the effect that his result will have on determining the outcome of the match. Unfortunately, this did not occur to me until Ekrem was low on time and I did not know what the correct procedure was for going about it. As a result, I had to talk to Mr. Barrett about it and before we could get it figured out, the players had agreed to the draw.

Ideally, a player should always try to apprise himself of how the match stands before he agrees to a draw. IHSA rules also permit a player to have the steward pass a Communication Card to a coach in order to find out how the match stands. Moreover, a player can initiate a communication regardless of how many games are still being played in the match. A player can also get up and look at the match score sheet. However, a player with less than four minutes on his clock cannot reasonably be criticized if he decides that trying to figure out how the match stands is not a wise use of his remaining time.

Mr Barrett and I should have been prepared to communicate the score if the need arose.

Why Game 60 Sucks

Game 60 is a convenient time control if you want to hold a match after the school day ends without getting the players home so late that they can't have dinner and do their homework. G60 is also handy if you want to complete a seven round tournament for the state championship in two days. However, when it comes to developing endgame technique, G60 sucks. On those rare occasions where both sides play well enough to reach an endgame where the result is in doubt, it is even rarer for either player to have enough time remaining to do the position justice. On top of that, players are often so low on time that they quit keeping score in the ending making it very difficult to go over the game and learn from mistakes.

One of the best reasons for joining the United States Chess Federation is to get the opportunity to play in some longer time controls. The Continental Chess Association runs three area events each year, the Chicago Open, the Chicago Class, and the Midwest Class, that use a time control of forty moves in two hours filed by one hour sudden death (40/2, SD/1). That means that each side has up to three hours to complete the game which usually leaves enough time to devote some thought to the ending. The Illinois Open, the Illinois Class, and Tim Just's Winter Open use game in ninety minutes with a thirty second increment (G90 inc 30) which means that thirty seconds get added to each players clock on each move. In a game that goes sixty moves, each side will have two hours. This doesn't always leave time for deep thought in the ending but at least the thirty seconds per move allows the player to keep score for later review. Up in Madison at the University of Wisconsin Chess Club, they occasionally run events with a generous 45/2, 25/1, SD/1.

The downside to the USCF events is that the longer time controls tend to be bigger events with larger entry events. Nevertheless, the key to improvement in all phases of the game is to play slower games.

The Zwischenzug

Despite Ekrem's professed lack of confidence in his endgame skills, he actually found a couple of moves that demonstrate excellent chess thinking. "Zwischenzug" is a German word meaning "in between move." It refers to a quiet move that is played in an otherwise forcing sequence. They are very easy to overlook when calculating variations. Ekrem found a very nice one on his 36th move.

The most obvious move here is 36.Rxb5 when Black will find it very difficult to promote his remaing h-pawn. Running low on time, no one could blame White for playing this move immediately. However, Ekrem saw that 36...Rxc2 threatened both White's a-pawn and f-pawn. He also saw that the Black b-pawn wasn't going anywhere so he played the zwischenzug 36.Re5! driving the bishop away from e1. After 36...Bd2 37.Rxb5 Rxc2, White could play 38.a4 without worrying about his f-pawn. This is the kind of thinking that produces good endgame play.

Basic Endgame Positions

In order to succeed in endings at short time controls, it is necessary to have some of the basic positions down pat such as The Wrong Colored Bishop and Rook Pawn. A lone king can draw against a king, bishop and a-pawn or king, bishop, and h-pawn if the bishop does not control the queening square.

This is the position that White would have had with both rooks and all his pawns gone. It is a draw because there is no way that Black will ever be able to evict the White king from h1. The quick reason that Ekrem should have kept playing is that even if he managed to lose all five of his pawns, all White needed to do was trade rooks in order to reach a dead drawn position.

Labels:

Drawing Techniques,

Endgames,

Fremd,

Zwischenzug

Friday, October 28, 2011

Prospect Falls to Fremd (1): Revisiting the Fried Liver Attack

After winning the Mid-Suburban League conference tournament last year and finishing 18th at state, Prospect had high hopes for this season, but the competition is proving very tough. On Thursday, Prospect fell to Fremd 36.5 to 31.5. Robert Moskwa on 1st Board and Mike Monsen on 3rd Board continued their winning ways and Prospect got its first win on 8th Board from Brett Abraham. Unfortunately, Ekrem Genc's draw on 4th Board left Prospect short.

Happily for me, there are many teachable moments to blog about:

Defending Against 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 2.Nc6 3.Bc4.

The most natural response to 1.e4 is 1...e5. After the equally natural moves 2.Nf3 Nc6, White has the choice of several systems. One of the sharpest is 3.Bc4 which immediately targets f7 which is Black's weakest square.

The Two Knights Defense

Based on my experience the most popular response among high school players is 3...Nf6 which is known as the Two Knights Defense. The most popular move for White is then 4.Ng5. This violates the basic opening principle (or maybe just rule of thumb) which says that no piece should be moved twice until every piece is moved once. In this case however, the violation is justified by the fact that Black has no easy way to defend f7 against the dual threat of the knight and the bishop.

Black can if he wishes ignore the threat with 4...Bc5 which is known as the Traxler Gambit. This is very exciting, but completely sound. The recommended move is 4...d5, which blocks the bishop's attack on f7. However, Black faces another choice after 5 exd5.

Practice has shown that Black's best move here is the odd looking 5...Na5. This move also moves a piece twice when other pieces haven't moved once. On top of that, it places a knight on the edge of the board.

While the Two Knights with 5...Na5 is considered a perfectly sound approach, it is tough to play without a decent level of book knowledge It seems to me that it is an openings where the common opening rules of thumb (like not placing a knight on the edge of the board) get violated more often than usual. One main continuation goes 7.Bb5+ c6 8.dxc6 bxc8 9.Qf3.

These are not the easiest moves to find over the board in a sixty minute game if you haven't seen them before.

The Fried Liver Attack.

After the more natural looking 5...Nxd5, White has the option of playing the Fried Liver Attack where White sacrifices a knight for a pawn with 6.Nxf7 in order to expose the Black king and draw it out to the middle of the board. Apparently the name derives from the fact that Black frequently winds up as dead as a piece of liver.

The Fried Liver Attack is not necessarily winning for White but it is not easy for Black to defend after 6...Kxf7 7.Qf3+ when Black is forced to play 7...Ke6 in order to defend the knight on d5.

One possible continuation is 8. Nc3 Ncb4 9. Qe4 c6 10. a3 Na6 11. d4 Nac7. However, 6.d4, delaying the knight sacrifice may actually be a better move for White. This allows White to add his other bishop to the attack quickly and it turns out that Black doesn't have anything that particularly improves his defensive chances. For example 6...Be7 7.Nxg7 Kxg7 8.Qf3+ gives White a revved up Fried Liver.

The Italian Game

In the ten years that I have been coaching at Prospect, I may have seen the Fried Liver a dozen times in matches. To the best of my recollection, Black won most if not all of them. So what is Black to do if he doesn't want to allow the Fried Liver and he doesn't want to have to find a lot of counter-intuitive moves after 5...Na5? I've seen some players go for 3...h6 to prevent 4.Ng5, but neglecting development isn't a good idea. My preference is simply 3...Bc5 leading to the Giuoco Piano aka the Italian Game.

Now 4.Ng5?? simply loses the knight to 4...Qxg5. If White plays 4.0-0, after 4...Nf6, Black can meet 5.Ng5 with 5...0-0.

3...Bc5 doesn't eliminate the possibility that White may sacrifice material to get a nasty attack. 4.b4 is the Evans Gambit which can be very tricky to handle. However, White often plays more quietly with 4.0-0 or 4.d3 and even if he chooses a more aggressive line, overall I think opening principles are violated much less frequently than in the Two Knights.

To sum up: After 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3. Bc4

Defending Against 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 2.Nc6 3.Bc4.

The most natural response to 1.e4 is 1...e5. After the equally natural moves 2.Nf3 Nc6, White has the choice of several systems. One of the sharpest is 3.Bc4 which immediately targets f7 which is Black's weakest square.

The Two Knights Defense

Based on my experience the most popular response among high school players is 3...Nf6 which is known as the Two Knights Defense. The most popular move for White is then 4.Ng5. This violates the basic opening principle (or maybe just rule of thumb) which says that no piece should be moved twice until every piece is moved once. In this case however, the violation is justified by the fact that Black has no easy way to defend f7 against the dual threat of the knight and the bishop.

Black can if he wishes ignore the threat with 4...Bc5 which is known as the Traxler Gambit. This is very exciting, but completely sound. The recommended move is 4...d5, which blocks the bishop's attack on f7. However, Black faces another choice after 5 exd5.

Practice has shown that Black's best move here is the odd looking 5...Na5. This move also moves a piece twice when other pieces haven't moved once. On top of that, it places a knight on the edge of the board.

While the Two Knights with 5...Na5 is considered a perfectly sound approach, it is tough to play without a decent level of book knowledge It seems to me that it is an openings where the common opening rules of thumb (like not placing a knight on the edge of the board) get violated more often than usual. One main continuation goes 7.Bb5+ c6 8.dxc6 bxc8 9.Qf3.

These are not the easiest moves to find over the board in a sixty minute game if you haven't seen them before.

The Fried Liver Attack.

After the more natural looking 5...Nxd5, White has the option of playing the Fried Liver Attack where White sacrifices a knight for a pawn with 6.Nxf7 in order to expose the Black king and draw it out to the middle of the board. Apparently the name derives from the fact that Black frequently winds up as dead as a piece of liver.

The Fried Liver Attack is not necessarily winning for White but it is not easy for Black to defend after 6...Kxf7 7.Qf3+ when Black is forced to play 7...Ke6 in order to defend the knight on d5.

One possible continuation is 8. Nc3 Ncb4 9. Qe4 c6 10. a3 Na6 11. d4 Nac7. However, 6.d4, delaying the knight sacrifice may actually be a better move for White. This allows White to add his other bishop to the attack quickly and it turns out that Black doesn't have anything that particularly improves his defensive chances. For example 6...Be7 7.Nxg7 Kxg7 8.Qf3+ gives White a revved up Fried Liver.

The Italian Game

In the ten years that I have been coaching at Prospect, I may have seen the Fried Liver a dozen times in matches. To the best of my recollection, Black won most if not all of them. So what is Black to do if he doesn't want to allow the Fried Liver and he doesn't want to have to find a lot of counter-intuitive moves after 5...Na5? I've seen some players go for 3...h6 to prevent 4.Ng5, but neglecting development isn't a good idea. My preference is simply 3...Bc5 leading to the Giuoco Piano aka the Italian Game.

Now 4.Ng5?? simply loses the knight to 4...Qxg5. If White plays 4.0-0, after 4...Nf6, Black can meet 5.Ng5 with 5...0-0.

3...Bc5 doesn't eliminate the possibility that White may sacrifice material to get a nasty attack. 4.b4 is the Evans Gambit which can be very tricky to handle. However, White often plays more quietly with 4.0-0 or 4.d3 and even if he chooses a more aggressive line, overall I think opening principles are violated much less frequently than in the Two Knights.

To sum up: After 1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3. Bc4

- The Two Knights Defense 3...Nf6 is perfectly sound however after White's most common move, 4.Ng5, Black is likely to wind up in tricky positions that are hard to play without some prior study.

- 3...Bc5 is also perfectly sound and the odds of Black reaching a position that requires less book knowledge is much greater.

Friday, October 14, 2011

Thursday, October 13, 2011

Prospect v. Hoffman: An Important Drawing Technique

Prospect lost for the first time this season to Hoffman Estates, 46-22. Prospect had winning chances on 4th and 7th Boards and drawing chances on 3rd and 6th, but was unable to convert.

The drawing chances on 6th came in a position similar to this. If White is to move here, he wins easily with 1.Rd6+. However, if it's Black's move, he draws with 1...Qc3+ 2.Kb1 Qb3+ 3.Kc1 Qc3+. White has no way to escape the queen checks as long as Black keeps his queen on the same file as the White queen. Unfortunately, in the match White played 3...Qa3+? which allowed the White king to get to safety with 4.Kd2.

The drawing chances on 6th came in a position similar to this. If White is to move here, he wins easily with 1.Rd6+. However, if it's Black's move, he draws with 1...Qc3+ 2.Kb1 Qb3+ 3.Kc1 Qc3+. White has no way to escape the queen checks as long as Black keeps his queen on the same file as the White queen. Unfortunately, in the match White played 3...Qa3+? which allowed the White king to get to safety with 4.Kd2.

Tuesday, October 11, 2011

Is It Safe?

Hey! You guys on the lower boards . . .

STOP HANGING YOUR PIECES!!!!

Ahhh . . . It felt good to get that out of my system.

There are very few players in the Mid-Suburban League who do not hang a piece from time to time, but the players on the upper boards do it much less frequently than the players on the lower boards. When a 1st or 2nd Board hangs a piece it is usually because he overlooked an attack on his piece. when a 7th or 8th Board hangs a piece, it is often because piece safety is not a habitual part of his thought process. The 7th or 8th Board may be perfectly capable of figuring out whether a piece is safe or not, but he only bothers to do so intermittently.

As usual, my favorite source of advice is Dan Heisman's Novice Nook column at ChessCafe.com I recommend reading The Safety Table.

Sunday, October 9, 2011

Prospect v. Palatine: Pieces Before Pawns

Prospect beat Palatine 57-11 in its second match of the season. Although normally one of the toughest teams in the conference, Palatine lost many of its upper boards from last year to graduation.

It's always nice when a principle I write about in one post is perfectly illustrated in a game from the next match. In my last post, I stressed the need to improve the position of pieces before pushing pawns in the endgame. That principle arose again on third board where Palatine's Karan Patel had White against Prospect's Ekrem Genc. At first glance, it appears that the Black rook can pick off the White pawns at its leisure, however, White can still draw the game with 46.Kf4! After 46...Rg8 47.Ke5 Rxg7 48.Kd5 Rb7 49.Kc5, the White king has just enough time to protect the b-pawn. Since the Black king is to far away to help, the game will be drawn after Black is forced to give up his rook to stop the pawn from queening.

In the game, however, White pushed with 46.b6? which leaves the White king with insufficient time to come to the aid of either of the pawns. White lost after 46...Rg8 47.b7 Rxg7+ 48.Kf4 Rxb7.

It's always nice when a principle I write about in one post is perfectly illustrated in a game from the next match. In my last post, I stressed the need to improve the position of pieces before pushing pawns in the endgame. That principle arose again on third board where Palatine's Karan Patel had White against Prospect's Ekrem Genc. At first glance, it appears that the Black rook can pick off the White pawns at its leisure, however, White can still draw the game with 46.Kf4! After 46...Rg8 47.Ke5 Rxg7 48.Kd5 Rb7 49.Kc5, the White king has just enough time to protect the b-pawn. Since the Black king is to far away to help, the game will be drawn after Black is forced to give up his rook to stop the pawn from queening.

In the game, however, White pushed with 46.b6? which leaves the White king with insufficient time to come to the aid of either of the pawns. White lost after 46...Rg8 47.b7 Rxg7+ 48.Kf4 Rxb7.

Wednesday, October 5, 2011

Endgames: Position Pieces Prior to Pushing Pawns

The most common mistake I see players on the lower boards make in the endgames is pushing pawns before their pieces are in a position to support the advance. Sometimes the game does come down to a race between unobstructed pawns, but I think it is much more common that a pawn will need support to advance. A player should always ask himself whether he needs to improve the position of his pieces before pushing a passed pawn.

This position occurred on 5th Board in the Conant match. White has an extra passed a-pawn, but all three of Black's pieces are well positioned to oppose its advance. The only piece supporting the pawn is the White rook, but since it is front of the pawn, it will have to move off the a-file in order for the pawn to reach the queening square at which point the pawn will be completely unprotected. Since the a-pawn is perfectly secure on its present square, White's first priority should be to get his king and knight involved in the game. Bringing the knight to c4 via e3 is one obvious plan.

The game eventually reached a king and pawn ending. The winning technique here is for White to get his king in front of his pawn with 57.Kg5 Kf7 58.Kh6 Kg8 59.Kg6 Kh8 60.g5 Kg8 61.Kh6 Kh8 62.g6 Kg8 63.g7 Kf7 64.Kh7 and the pawn queens. After 57.g5, which White played, Black should have been able to draw with 57...Kf7 58.Kh5 Kg7 59.g6 as long as he remembered that Straight Back Draws 59...Kg8 60.Kh6 Kh8 61.g7+ Kg8 62.Kg6 stalemate.

This endgame occurred on 6th Board against Conant. It should be a fairly easy win for Black. In an open position with pawns on both sides of the board, the rook is a much stronger piece than the knight. All Black needs to do is to find a square for the rook that maximizes its attacking capabilities. Any square on the 2nd rank would give the rook many targets. 26...Re1 is a logical way to start.

Unfortunately, Black chose to advance pawns instead. Rooks are much better at attacking than defending. Even after several pawn moves, Black still could have gone on the offensive with 32...Rd2.

In this final position, the Black pawn doesn't need any support, but Black still needs to improve his piece before pushing it. In the game, Black played 50...b3? and lost after 51.a7 b2 52.a8=Q+ Ke7 53.Qa2. Black could have won with 50...Kb8! 51.a7+ Ka8 52.c5 b3 53.c6 b2 57.c7 b1=Q+.

This position occurred on 5th Board in the Conant match. White has an extra passed a-pawn, but all three of Black's pieces are well positioned to oppose its advance. The only piece supporting the pawn is the White rook, but since it is front of the pawn, it will have to move off the a-file in order for the pawn to reach the queening square at which point the pawn will be completely unprotected. Since the a-pawn is perfectly secure on its present square, White's first priority should be to get his king and knight involved in the game. Bringing the knight to c4 via e3 is one obvious plan.

The game eventually reached a king and pawn ending. The winning technique here is for White to get his king in front of his pawn with 57.Kg5 Kf7 58.Kh6 Kg8 59.Kg6 Kh8 60.g5 Kg8 61.Kh6 Kh8 62.g6 Kg8 63.g7 Kf7 64.Kh7 and the pawn queens. After 57.g5, which White played, Black should have been able to draw with 57...Kf7 58.Kh5 Kg7 59.g6 as long as he remembered that Straight Back Draws 59...Kg8 60.Kh6 Kh8 61.g7+ Kg8 62.Kg6 stalemate.

This endgame occurred on 6th Board against Conant. It should be a fairly easy win for Black. In an open position with pawns on both sides of the board, the rook is a much stronger piece than the knight. All Black needs to do is to find a square for the rook that maximizes its attacking capabilities. Any square on the 2nd rank would give the rook many targets. 26...Re1 is a logical way to start.

Unfortunately, Black chose to advance pawns instead. Rooks are much better at attacking than defending. Even after several pawn moves, Black still could have gone on the offensive with 32...Rd2.

In this final position, the Black pawn doesn't need any support, but Black still needs to improve his piece before pushing it. In the game, Black played 50...b3? and lost after 51.a7 b2 52.a8=Q+ Ke7 53.Qa2. Black could have won with 50...Kb8! 51.a7+ Ka8 52.c5 b3 53.c6 b2 57.c7 b1=Q+.

Labels:

Conant,

Endgames,

Pieces Before Pawns,

Straight Back Draws

Friday, September 30, 2011

Prospect v. Conant: Putting the Horse in the Corral

The third veteran to come through in the Conant match was sophomore Mike Monsen on 2nd Board. Although tactically a little rusty from the summer layoff, Mike played a very solid game positionally. The ending from the game provides a good example of the way that a bishop can dominate a knight in an ending.

While watching the game, I liked the idea of taking the c1 square away from the Black knight with 41.Be3 when Black will be forced to give up a pawn to extract his knight with either 41...c5 42.Kc3 Na5 43.Bxc5 or 41...b5 42.cxb5 cxb5 43.Kc3 Na5 44.Kb4 Nc4 45.Bd4 Nd6 46.Kc5 Nb7+ 47.Kxb5. The knight would be trapped after 41...Na5 42.b4 Nb3 43.Kc3 Na1 44.Kb2.

The computer indicates that 41. Kc2! is an even stronger way to confine the knight. 41...Na5 42.c5 Nc4 43.Bd4.

The only way Black can save the knight is by giving up the b-pawn. 43...b5 44.cxb6 (Don't forget en passant!) Nd6. 41.Be3 merely wins a second pawn. 41.Kc2! wins a second pawn on the 6th rank.

In the game Mike played 41.Kc3 and the Black knight managed to slip away to a secure spot via c1-e2-f4. Happily, Mike's technique was more than sufficient to win with only one extra pawn.

While watching the game, I liked the idea of taking the c1 square away from the Black knight with 41.Be3 when Black will be forced to give up a pawn to extract his knight with either 41...c5 42.Kc3 Na5 43.Bxc5 or 41...b5 42.cxb5 cxb5 43.Kc3 Na5 44.Kb4 Nc4 45.Bd4 Nd6 46.Kc5 Nb7+ 47.Kxb5. The knight would be trapped after 41...Na5 42.b4 Nb3 43.Kc3 Na1 44.Kb2.

The computer indicates that 41. Kc2! is an even stronger way to confine the knight. 41...Na5 42.c5 Nc4 43.Bd4.

The only way Black can save the knight is by giving up the b-pawn. 43...b5 44.cxb6 (Don't forget en passant!) Nd6. 41.Be3 merely wins a second pawn. 41.Kc2! wins a second pawn on the 6th rank.

In the game Mike played 41.Kc3 and the Black knight managed to slip away to a secure spot via c1-e2-f4. Happily, Mike's technique was more than sufficient to win with only one extra pawn.

Wednesday, September 28, 2011

Prospect v. Conant: The Veterans Come Through

Here are a couple more games from the Prospect-Conant match. On 1st Board, Caleb Royse won a piece in the opening and kept a tight grip on the position throughout the entire game. His opponent really never had any counterplay. On 3rd Board, Ekrem Genc built a very solid position out of the opening but blundered away a knight on the 19th move. However, because Echo had a good position before the error, it was not easy for his opponent to consolidate his advantage. When he failed to find the best move, Echo quickly took advantage.

Prospect v. Conant: Fast Freshmen Face First Foes

Prospect opened the 2011-2012 season with a 41-27 victory at Conant. With Robert Moskwa unavailable, Caleb Royse played 1st Board for the first time and Mike Monsen and Ekrem Genc moved up three boards from last year to 2nd and 3rd. On 4th through 6th Boards, Prospect fielded freshmen Kyle Gilligan, Marc Graff, and Alexander Johnson. While a junior, Giovani Roldan was also new to chess club and playing in his first match. Prospect started 5 points in the hole when it forfeited 8th Board and faced a 27-0 deficit after three of its newcomers lost quickly. However, Mark Graff managed a win on 5th Board and the three returning players all won their games to give Prospect the win.

Freshman Futility.

I well remember my first visit to the high school chess club as a freshman exactly thirty years ago. I had learned the game at home and I held my own pretty well against my older brothers so I was optimistic about my chances. That didn't last very long. I was slaughtered in game after game. After a few visits, I gave up on chess and didn't return for the rest of the year.

During the summer between my freshman and sophomore years, Bobby Fischer played Boris Spassky for the World Chess Championship and for a brief shining moment, chess was cool in the United States. A good friend of mine became interested in the match and we played through the game scores that appeared in the newspaper. We also watched some of the games on public television where a master would analyze the games.

While most of the analysis was way over my head, it was clear to me that real chess players thought through their moves in ways that had never occurred to me. They did not play the first move that came into their heads and hope that something good would happen. They considered all their possible moves and spent time trying to figure out how their opponent might reply to each one. Real chess players played real chess.

When school started again, my friend and I both joined the chess club and we managed to move up to 3rd and 4th Boards by the end of the year.

The Newcomers at Conant

The performance of Prospect's newcomers was pretty typical for players in their first match.

(1) They played much too quickly. All of them had made twenty moves before five minutes were gone from their clock. Often they took no more than a few seconds to think about their moves.

(2) They did not think about what their opponent was threatening.

(3) They played the first move that occurred to them without thinking about alternatives.

(4) They did not try to figure out how their opponent was likely to respond to the move they were considering.

Here are a couple examples of what I'm talking about from the game on 5th Board between Marc Graff and Ming Tsai:

The game began 1.e4 d5.

Question: What is Black threatening?

Answer: 2...dxe4 winning a pawn.

Question: How can White deal with that threat?

Answer #1: Capture the attacking pawn with 2.exd5. This is considered best.

Answer #2: Move the pawn that is being attacked with 2.e5. This is reasonable.

Answer #3: Protect the pawn that is being attacked with 2.d3 or 2.Nc3. These are rather passive.

What White actually played was 2.Nf3? which just loses a pawn.

Question: Why did White play this move?

Answer: Although I don't know for sure, my guess would be that he made his move automatically without thinking about what his opponent had done. He might have expected his opponent to play 1...e5 which is much more common than 1...d5. After 1...e5, the best move is 2.Nf3. 2.Nf3 is also the best move against 1...c5. 2.Nf3 is also a perfectly playable move against 1...e6, 1...c6 and 1...d6, and 1...Nc6. 2.Nf3 is only bad if Black plays 1...d5 or 1...Nf6 because those moves threaten the White pawn on e4.

(I will confess that I have played 2.Nf3? in the same situation, however, I did it in a one-minute blitz game on the internet.)

Question: What is Black threatening?

Answer: 17...Nex4 winning the e-pawn.

Question: How can White deal with that threat?

Answer #1: Capture the attacking piece with 17.Qxc5?? This is terrible due to 17...Qxc5.

Answer #2: Protect the pawn that is being attacked with 17.f3.

Answer #3: Force Black to deal with a more serious threat by attacking the Black queen with either 17. Nf5 or 17.Rd1, which is what White played in the game, which was followed by 17...Nxe4 18.Rxd6 Nxc3 19.Rxc6.

Question: Which is stronger, 17.Nf5 or 17.Rd1?

Answer: 17.Nf5. If Black plays 17...Nxe4??, White plays 18.Nxd6+! After 18...exd6, White moves his queen to safety. Black must move his queen an the knight on c5 will be unprotected, e.g., 17...Qe6 18.Qxc5.

Question: Why did White play 17.Rd1?

Answer: I don't know for sure, but my guess would be that he saw that move first and did not take the time to think about other possibilities. To be clear, 17.Rd1 was not a bad move, however, there was a much better move available and White had plenty of time to evaluate alternatives.

Casual Chess vs. Serious Chess.

Chess can be a very unforgiving game. If you make a mistake in a tennis match, you can forget about it and move on to the next point. If you make a mistake in chess, however, you are stuck with the consequences for the rest of the game. Lose a piece and you may never have the chance to get it back. Allow a back rank mate and the game is over.

In serious chess, you have to think on every move. You have to look for your opponents threats. You have to consider your alternatives. Most importantly, you have to think about your opponent's best response to the move you are thinking about playing.

The good news is that every time you put in the effort, your understanding of the game will increase. Patterns and tactics will become familiar to you. You will learn to spot your opponents threats and anticipate responses to your moves more quickly.

Freshman Futility.

I well remember my first visit to the high school chess club as a freshman exactly thirty years ago. I had learned the game at home and I held my own pretty well against my older brothers so I was optimistic about my chances. That didn't last very long. I was slaughtered in game after game. After a few visits, I gave up on chess and didn't return for the rest of the year.

During the summer between my freshman and sophomore years, Bobby Fischer played Boris Spassky for the World Chess Championship and for a brief shining moment, chess was cool in the United States. A good friend of mine became interested in the match and we played through the game scores that appeared in the newspaper. We also watched some of the games on public television where a master would analyze the games.

While most of the analysis was way over my head, it was clear to me that real chess players thought through their moves in ways that had never occurred to me. They did not play the first move that came into their heads and hope that something good would happen. They considered all their possible moves and spent time trying to figure out how their opponent might reply to each one. Real chess players played real chess.

When school started again, my friend and I both joined the chess club and we managed to move up to 3rd and 4th Boards by the end of the year.

The Newcomers at Conant

The performance of Prospect's newcomers was pretty typical for players in their first match.

(1) They played much too quickly. All of them had made twenty moves before five minutes were gone from their clock. Often they took no more than a few seconds to think about their moves.

(2) They did not think about what their opponent was threatening.

(3) They played the first move that occurred to them without thinking about alternatives.

(4) They did not try to figure out how their opponent was likely to respond to the move they were considering.

Here are a couple examples of what I'm talking about from the game on 5th Board between Marc Graff and Ming Tsai:

The game began 1.e4 d5.

Question: What is Black threatening?

Answer: 2...dxe4 winning a pawn.

Question: How can White deal with that threat?

Answer #1: Capture the attacking pawn with 2.exd5. This is considered best.

Answer #2: Move the pawn that is being attacked with 2.e5. This is reasonable.

Answer #3: Protect the pawn that is being attacked with 2.d3 or 2.Nc3. These are rather passive.

What White actually played was 2.Nf3? which just loses a pawn.

Question: Why did White play this move?

Answer: Although I don't know for sure, my guess would be that he made his move automatically without thinking about what his opponent had done. He might have expected his opponent to play 1...e5 which is much more common than 1...d5. After 1...e5, the best move is 2.Nf3. 2.Nf3 is also the best move against 1...c5. 2.Nf3 is also a perfectly playable move against 1...e6, 1...c6 and 1...d6, and 1...Nc6. 2.Nf3 is only bad if Black plays 1...d5 or 1...Nf6 because those moves threaten the White pawn on e4.

(I will confess that I have played 2.Nf3? in the same situation, however, I did it in a one-minute blitz game on the internet.)

Question: What is Black threatening?

Answer: 17...Nex4 winning the e-pawn.

Question: How can White deal with that threat?

Answer #1: Capture the attacking piece with 17.Qxc5?? This is terrible due to 17...Qxc5.

Answer #2: Protect the pawn that is being attacked with 17.f3.

Answer #3: Force Black to deal with a more serious threat by attacking the Black queen with either 17. Nf5 or 17.Rd1, which is what White played in the game, which was followed by 17...Nxe4 18.Rxd6 Nxc3 19.Rxc6.

Question: Which is stronger, 17.Nf5 or 17.Rd1?

Answer: 17.Nf5. If Black plays 17...Nxe4??, White plays 18.Nxd6+! After 18...exd6, White moves his queen to safety. Black must move his queen an the knight on c5 will be unprotected, e.g., 17...Qe6 18.Qxc5.

Question: Why did White play 17.Rd1?

Answer: I don't know for sure, but my guess would be that he saw that move first and did not take the time to think about other possibilities. To be clear, 17.Rd1 was not a bad move, however, there was a much better move available and White had plenty of time to evaluate alternatives.

Casual Chess vs. Serious Chess.

Chess can be a very unforgiving game. If you make a mistake in a tennis match, you can forget about it and move on to the next point. If you make a mistake in chess, however, you are stuck with the consequences for the rest of the game. Lose a piece and you may never have the chance to get it back. Allow a back rank mate and the game is over.

In serious chess, you have to think on every move. You have to look for your opponents threats. You have to consider your alternatives. Most importantly, you have to think about your opponent's best response to the move you are thinking about playing.

The good news is that every time you put in the effort, your understanding of the game will increase. Patterns and tactics will become familiar to you. You will learn to spot your opponents threats and anticipate responses to your moves more quickly.

Wednesday, September 7, 2011

Bishop v. Knight at the 2011 Illinois Open

The most frustrating thing about taking up a new opening is when no one will let you play it. I decided to try playing 1...e5 in response to 1.e4 earlier this year, but I only had one chance to do so at the Chicago Open and no chances at the MAC July Swiss. At the Illinois Open, however, my luck changed and I faced 1.e4 all three times with the Black pieces and I won all three games. Unfortunately, I could only manage a single draw out of three games with the White pieces which may be my worst relative performance with the White pieces in a tournament ever. Of course, part of the disparity was due to the fact that average rating of the opponents' I faced with White was 2180 versus 1837 with Black.

In two of the games with the Black pieces I faced sidelines in the Ruy Lopez that I haven't gotten around to studying yet. In one of the games, I managed to come up with the plan recommended by the books and in one I didn't, but in both games I wound with two bishops against two knights as compensation for a damaged pawn structure.

Bishops v. Knights

Novice chess players are usually taught that knights and bishops are equally strong pieces so that trading one for another is an even swap. However, I have run across many high school players who view the knight as much more dangerous. I suspect that this is because the knight's move is more difficult to visualize and they tend to show up on unexpected squares to deliver nasty forks. Many young players will happily trade their bishops for their opponents knights at the first opportunity.

At higher levels, bishops are thought to be slightly stronger pieces, although the features of any given position determine which one is superior. The bishop does well in positions where it has open diagonals upon which to operate. In a position blocked with pawns, knight's ability to leap over pieces and pawns may give it the advantage. A knight is happiest when it has a secure outpost where it is defended by a pawn. (One thing to keep in mind is that blocked positions often open up, while the opposite rarely occurs). In an ending where there are pawns on both sides of the board, the bishop tends to dominate due to it's ability to operate at long range, but when the action is confined to one side, the knight's ability to attack squares of both colors may be key. Queen's and knights tend to work well together while the bishop would prefer to be paired with a rook.

One of the things that makes a bishop very handy in an ending is its superior ability to make a waiting move. Whenever a knight moves, it no longer protects or attacks any of the pawns it protected or attacked before it moved. If the knight is preventing an opponent's king from advancing to a more favorable square, it won't be after it moves. When a bishop moves along a diagonal, on the other hand, it still can still cover squares on that diagonal.

The position I reached in the 1st round of the Illinois Open illustrates some of bishop's advantages. Although Whites is down a pawn, one might think at first glance that his nicely centralized king and superior pawn structure might give him some chances to draw. In fact, it is a pretty easy win for Black. There is no way for the White knight to get at any of the Black pawns, and the Black bishop easily forces the White pieces to give way. The game continued 42.Nb1 c5+ 43.Kc3 Kd5 44.Nd2 Be2! (Just in case the knight had any thoughts about heading over to the king side via f3 and h4) 45. Nb3 Kc6 46.Nc1 Bf1 47. Nb3 Kb5 and the White a-pawn fell.

In the 4th round, the bishops proved their superiority in the middle game. My opponent played the Exchange Variation of the Ruy Lopez but the long distance power of my bishops prevented his knights from ever getting passed the third rank. When knights are forced to defend each other it is usually a sign of a passive position. The game finished 33.a3 Be5+ 34.Ka2 Kc3 35.Rd1 Re3 36.Rf2 Rd8 37.f4 Bxd3 38 fxg5 Bb1+ 39.Kxb1 Rxd1 0-1.

In two of the games with the Black pieces I faced sidelines in the Ruy Lopez that I haven't gotten around to studying yet. In one of the games, I managed to come up with the plan recommended by the books and in one I didn't, but in both games I wound with two bishops against two knights as compensation for a damaged pawn structure.

Bishops v. Knights

Novice chess players are usually taught that knights and bishops are equally strong pieces so that trading one for another is an even swap. However, I have run across many high school players who view the knight as much more dangerous. I suspect that this is because the knight's move is more difficult to visualize and they tend to show up on unexpected squares to deliver nasty forks. Many young players will happily trade their bishops for their opponents knights at the first opportunity.

At higher levels, bishops are thought to be slightly stronger pieces, although the features of any given position determine which one is superior. The bishop does well in positions where it has open diagonals upon which to operate. In a position blocked with pawns, knight's ability to leap over pieces and pawns may give it the advantage. A knight is happiest when it has a secure outpost where it is defended by a pawn. (One thing to keep in mind is that blocked positions often open up, while the opposite rarely occurs). In an ending where there are pawns on both sides of the board, the bishop tends to dominate due to it's ability to operate at long range, but when the action is confined to one side, the knight's ability to attack squares of both colors may be key. Queen's and knights tend to work well together while the bishop would prefer to be paired with a rook.

One of the things that makes a bishop very handy in an ending is its superior ability to make a waiting move. Whenever a knight moves, it no longer protects or attacks any of the pawns it protected or attacked before it moved. If the knight is preventing an opponent's king from advancing to a more favorable square, it won't be after it moves. When a bishop moves along a diagonal, on the other hand, it still can still cover squares on that diagonal.

The position I reached in the 1st round of the Illinois Open illustrates some of bishop's advantages. Although Whites is down a pawn, one might think at first glance that his nicely centralized king and superior pawn structure might give him some chances to draw. In fact, it is a pretty easy win for Black. There is no way for the White knight to get at any of the Black pawns, and the Black bishop easily forces the White pieces to give way. The game continued 42.Nb1 c5+ 43.Kc3 Kd5 44.Nd2 Be2! (Just in case the knight had any thoughts about heading over to the king side via f3 and h4) 45. Nb3 Kc6 46.Nc1 Bf1 47. Nb3 Kb5 and the White a-pawn fell.

In the 4th round, the bishops proved their superiority in the middle game. My opponent played the Exchange Variation of the Ruy Lopez but the long distance power of my bishops prevented his knights from ever getting passed the third rank. When knights are forced to defend each other it is usually a sign of a passive position. The game finished 33.a3 Be5+ 34.Ka2 Kc3 35.Rd1 Re3 36.Rf2 Rd8 37.f4 Bxd3 38 fxg5 Bb1+ 39.Kxb1 Rxd1 0-1.

Tuesday, June 21, 2011

MAC June Swiss

On Saturday June 18, Prospect 1st Board Robert Moskwa and I played in a four round G60 in Elgin run by the McHenry Area Chess Association. I managed to give back 20 of the rating points I picked up at the Chicago Open by failing to find the winning move in the first round against 1766 rated Tim Ailes.

As Robert pointed out on the way home, 46.Nxe6! Ke7 47.Ra6 wins. Unfortunately, I thought that I would just drop the d-pawn because I didn't notice that the Black bishop was hanging. So I played 46.Rxd4 which lost painfully to 46...f5! I followed this up with a loss to Expert Larry Cohen.

Robert, on the other hand, had another fine performance. After a first round bye and a loss to 1959 rated Joe Cima, he finished with wins against 1798 rated Caleb Larsen and 1904 rated Chris Baumgartner. This gained him another 57 points to bring his rating to 1830 after only 22 USCF rated games. After I returned to tournament chess in 1996, it took me 80 games to reach that point.

I did have the consolation of beating the 69th highest rated eleven-year old in the country, Haoyang Yu, when he tried to control the center with his pawns while neglecting his development. Haoyang opened with 1.d4 and I played the Nimzo-Indian Defense 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Bb4. White played the Classical variation 4.Qc2 which is currently the most popular approach among grandmasters. After, 4...0-0 5.a3 Bxc3+ 6.Qxc3 b6, he had achieved his goal of obtaining the bishop pair without weakening his pawn structure.

The problem for White is that his only developed piece is his queen, and he is still several moves away from castling. The most usual move here is to get on with development with 7.Bg5, but my opponent continued making pawn moves with 7.e3 Bb7 8. f3?! c5 9. d4?! cxd4 10.Qxd4 Nc6 11.Qd1.

White's pawns don't look bad, but after having played eleven moves, all his pieces are sitting on their original squares. Naturally, It is time for Black to open up the position. 11...d5 12.cxd5 exd5 13. Bd3 Nxe4! when White cannot play 14.Bxe4 due to 14...Bh4+. After 14.Nf3, I was able to use my superior development to win a second pawn and trade down to an easily won ending.

As Robert pointed out on the way home, 46.Nxe6! Ke7 47.Ra6 wins. Unfortunately, I thought that I would just drop the d-pawn because I didn't notice that the Black bishop was hanging. So I played 46.Rxd4 which lost painfully to 46...f5! I followed this up with a loss to Expert Larry Cohen.

Robert, on the other hand, had another fine performance. After a first round bye and a loss to 1959 rated Joe Cima, he finished with wins against 1798 rated Caleb Larsen and 1904 rated Chris Baumgartner. This gained him another 57 points to bring his rating to 1830 after only 22 USCF rated games. After I returned to tournament chess in 1996, it took me 80 games to reach that point.

I did have the consolation of beating the 69th highest rated eleven-year old in the country, Haoyang Yu, when he tried to control the center with his pawns while neglecting his development. Haoyang opened with 1.d4 and I played the Nimzo-Indian Defense 1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Bb4. White played the Classical variation 4.Qc2 which is currently the most popular approach among grandmasters. After, 4...0-0 5.a3 Bxc3+ 6.Qxc3 b6, he had achieved his goal of obtaining the bishop pair without weakening his pawn structure.

The problem for White is that his only developed piece is his queen, and he is still several moves away from castling. The most usual move here is to get on with development with 7.Bg5, but my opponent continued making pawn moves with 7.e3 Bb7 8. f3?! c5 9. d4?! cxd4 10.Qxd4 Nc6 11.Qd1.

White's pawns don't look bad, but after having played eleven moves, all his pieces are sitting on their original squares. Naturally, It is time for Black to open up the position. 11...d5 12.cxd5 exd5 13. Bd3 Nxe4! when White cannot play 14.Bxe4 due to 14...Bh4+. After 14.Nf3, I was able to use my superior development to win a second pawn and trade down to an easily won ending.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)